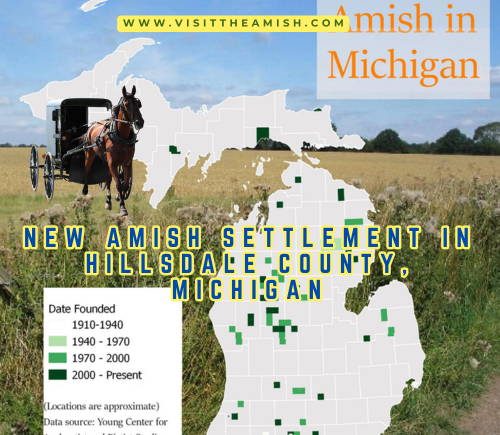

From Indiana to Michigan: New Amish Settlement Reshapes Rural Landscape

In the rolling hills of Hillsdale County, Michigan, a new chapter in Amish history is unfolding. The latest Amish settlement in the Great Lakes State has been steadily growing since its establishment in early 2024, bringing with it a rich tapestry of tradition, faith, and community values. This settlement, originating from Indiana, has now become a significant presence in the area, with approximately 20 families calling it home.

The decision to establish a new community in Michigan was not made lightly. Amos Yoder, one of the early settlers, explains, “We came seeking affordable farmland and a place to preserve our way of life. Hillsdale County has been very welcoming.” The move was driven by various factors, including increasing population pressures in their previous settlement and the desire to maintain traditional Amish lifestyles.

The impact of this new settlement on Hillsdale County has been profound. John Miller, a long-time resident of Jonesville, remarks, “It’s like watching history unfold before our eyes. The Amish have brought a sense of simplicity and purpose that’s refreshing in today’s fast-paced world.”

Indeed, the presence of the Amish has transformed the local landscape. The once-quiet country roads now regularly feature horse-drawn buggies, a sight that has become both a curiosity and a point of pride for many locals. Sarah Thompson, owner of a local farmers’ market, has noticed a significant change in the products available. “The Amish have introduced us to heirloom vegetables and traditional crafts that we hadn’t seen before. It’s been a boon for our market and our community,” she says.

The settlement has also brought economic benefits to the region. Mary Jenkins, head of the Hillsdale County Chamber of Commerce, notes, “We’ve seen a revival of traditional skills and craftsmanship. The Amish-made furniture, quilts, and food products are attracting tourists and boosting our local economy.”

However, the integration of the Amish community has not been without challenges. Sheriff David Brown explains, “We’ve had to implement new road safety measures to accommodate the horse-drawn buggies. It’s been a learning process for everyone, but we’re committed to ensuring the safety of all our residents, Amish and non-Amish alike.”

The Amish themselves have had to adapt to their new surroundings. Jacob Schwartz, an Amish farmer who moved from Indiana six months ago, shares his experience: “It took some time to get used to the Michigan soil and climate. But with hard work and the support of our community, we’ve managed to establish thriving farms and businesses.”

One of the most visible signs of the Amish presence in Hillsdale County is the increase in small, family-run businesses. From furniture workshops to produce stands, these enterprises have become integral to the local economy. Emma Miller, who runs a small bakery from her home, says, “We believe in the value of hard work and self-sufficiency. Our businesses allow us to support our families while staying true to our beliefs.”

Education has been another area of focus for the new settlement. The Amish have established a one-room schoolhouse where children are taught up to the eighth grade. Samuel Bontrager, an Amish teacher, explains, “Our school focuses on practical knowledge and moral values. We believe this approach best prepares our children for life in our community.”

The settlement’s growth has not gone unnoticed by state officials. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer recently visited the area and commented, “The Amish community in Hillsdale County exemplifies the values of hard work, family, and faith that we hold dear in Michigan. Their presence enriches our state’s cultural tapestry.”

As the settlement continues to grow, it faces both opportunities and challenges. Land prices in the area have increased, making it more difficult for young Amish families to establish their own farms. This has led to some diversification in occupations, with more Amish individuals taking up trades such as carpentry and masonry.

Environmental concerns have also come to the forefront. The Amish’s traditional farming methods, which often eschew modern chemical fertilizers and pesticides, have been praised by local environmentalists. However, issues such as manure management from horse-drawn buggies have required creative solutions.

Despite these challenges, the Amish community remains committed to their way of life. Bishop Eli Hochstetler, a community leader, states, “Our faith and our traditions have sustained us for generations. Here in Hillsdale County, we seek to continue that legacy while being good neighbors to those around us.”

The influence of the Amish settlement extends beyond Hillsdale County. It has inspired a renewed interest in sustainable living and traditional crafts among the wider population. Local schools have even begun incorporating field trips to Amish farms and workshops, providing students with hands-on learning experiences in agriculture and craftsmanship.

The establishment of this new Amish settlement in Hillsdale County is more than just a demographic shift; it’s a testament to the enduring appeal of a simpler way of life. As America grapples with the challenges of the 21st century, the Amish of Hillsdale County offer a living example of resilience, community, and faith – values that resonate far beyond the boundaries of their settlement.

Local resident Emily Johnson, who lives near the new settlement, shares her perspective: “At first, I was unsure about how this would change our community. But seeing the Amish families work together, their children playing in the fields, and the way they’ve revitalized some of our abandoned farms has been truly inspiring. They’ve brought a sense of peace and purpose to our area.”

The Amish settlement has also had an unexpected impact on local tourism. Tom Anderson, owner of a bed and breakfast in nearby Jonesville, reports a significant increase in bookings. “People are fascinated by the Amish way of life,” he explains. “They come here to experience a slice of living history, to slow down and reconnect with simpler values. It’s been great for business, but more importantly, it’s fostering understanding and respect between different ways of life.”

As the sun sets over the rolling hills of Hillsdale County, the sound of clip-clopping hooves and the sight of lantern-lit buggies serve as a reminder of the unique blend of past and present that this new Amish settlement represents. It’s a community that looks to the future while holding fast to the values of the past, weaving its story into the rich fabric of Michigan’s history.

Citations:

[1] https://www.localdifference.org/blog/amish-country-in-ne-michigan/

[2] https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-mi-defends-amish-communitys-religious-freedom-against-lenawee-countys-threat

[3] https://leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/leader.AEA.26082021.16/full/

[4] https://amishamerica.com/michigan-amish/

[5] https://www.aclumich.org/en/press-releases/aclu-defends-amish-communitys-religious-freedom-against-lenawee-countys-threat

[6] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367628476_Michigan_Amish_Fellowship_A_Case_Study_for_Defining_an_Amish_Affiliation

[7] https://www.aclumich.org/en/cases/county-threatens-religious-freedom-amish-community

[8] https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53a7697fe4b074c786349b42/1664320291272-9T5WEAFXS4DIJEHUQ1PC/Amish+-+1+of+1.jpeg?format=1500w&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj7yI6S5_eKAxVNv4kEHcvVLgAQ_B16BAgNEAI

Like this:

Like Loading...